Search Results

59 items found for ""

Blog Posts (36)

- Cumbre Vieja

The Cumbre Vieja is an active volcanic ridge on the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands, Spain. It reaches a height of 1,949 m above sea level at the vent of La Deseada. The spine of Cumbre Vieja trends in an approximate north–south direction, and covers the southern half of La Palma, with both summit ridge and flanks pockmarked by over a dozen craters. Since about 125,000 years ago (~125 ka), all subaerial eruptions on La Palma have been associated with the Cumbre Vieja, with eruptions ranging over the whole 25-kilometre-long ridge. Submarine surveys show that the Cumbre Vieja continues south of Punta de Fuencaliente (the "Point of the Hot Source"), but no volcanic activity connected with the submarine extension has yet been observed. Cumbre Vieja, meaning 'Old Summit', is in fact older than its younger counterpart Cumbre Nueva, which in turn means 'New Summit.' This paradox is owed to the fact that in mainland Spain, rugged mountain ranges with sharper summits—such as the Cantabrian Mountains—were traditionally referred to as 'new', whereas softer, eroded landscapes—such as the Galician Massif—were referred to as 'old'. While this naming system is geologically accurate in mainland Spain, it has lead to an incoherent interpretation in the Canary Islands. Due to orographic similarity and not because of their geological genesis, the older, rugged mountain ridges of La Palma—the Caldera de Taburiente and Cumbre Nueva—were considered to be new, and the softer mountain ranges pockmarked by recent volcano eruptions—Cumbre Vieja—were considered to be old. Prehistorical eruptions Eruptions in the last 7,000 years have originated from abundant cinder cones and craters along the axis of Cumbre Vieja, producing fissure-fed lava flows gushing abruptly to the sea. ~125 ka: Formation of the volcanic ridge of Cumbre Vieja. 6,050 BCE ± 1,500: Eruption. 4,900 BCE ± 50: Eruption. 4,050 BCE ± 3000: Eruption of l'Amendrita and Birigoyo. 1,320 BCE ± 100: Eruption of La Fajana. 360 BCE ± 50: Eruption of El Fraile. 900 CE ± 100: Eruption of Nambroque II-Malforada. Subhistorical and historical eruptions From the first contacts of the European navigators who first visited the Canary Islands around the 15th century, 18 eruptions have occurred, of which 7 took place on La Palma. They mostly produced light explosive activity and lava flows that damaged the populated areas. On every occasion, alcaline basaltic lavas were emitted: true basalts, ankaramites and/or basanitoids. A differentiation process always took place in the magma chamber and a sequence from amphibole to olivine-bearing lavas was erupted. These variations of the chemistry and mineralogy of the lavas were related to the different stages of the eruption and the height over sea level where the corresponding eruptive vents opened. The duration of these historic eruptions ranges between 1 and 3 months, and the area covered with lava and pyroclasts is 39 km², 5.5% of the total surface of the island. The 7 historic eruptions of La Palma have occurred in the southern half of the island, known as Cumbre Vieja, which spans from El Paso to the southernmost tip of the island in Fuencaliente. All eruptions began after a more or less prolonged period of earthquakes, whose magnitude never exceeded 6 on the Richter scale. These quakes were always restricted to some zones of the island, and increased their intensity and frequency on the days and hours preceding the eruptions. The eruption starts with the opening of little fissures of the ground following directions prefixed by the main structural patterns of the island. From the first moments, this fissuration is accompanied by the emission of gases and small lava fountains from several points along the whole extension of the main fissure that can attain several kilometers in length. Within a short time during the first hours of the event, these multiple incipient volcanic vents remain restricted to a few ones, increasingly active, where the construction of heaps of tephra increasingly grow and coalesce to the typical volcanic cones with their corresponding craters. When the fissure opens in a terrain with a considerable slope and in its direction, high pressure lava fountains, pyroclastic materials and gases are emitted from the higher volcanic vents, while from the lower vents only more or less degasified lava pours out with a much lower explosivity. This pattern is more noticeable when the difference in height of the volcanic vents is greater, and the duration of the eruption is long-lived. In the most typical instances, the higher vents grow to volcanic cones a couple of hundreds of meters, while in the lower ones, only some eruptive fissures with outpouring lava remain. This pattern is very clear in eruptions such as that of Tigalate, El Charco, San Juan and Tajogaite, where the difference in height of the vents is very noticeable. During the course of the eruption, it is also frequent that secondary cracks and fissures develop near the main volcanic vents, following also the main structural trends of the island. The eruption continues with changes in the activity of the several vents, until suddenly and without a marked and gradual decrease of the explosivity and lava outpour, the activity practically ceases. Subsequently, the entire eruptive area suffers a period of slow degasification, gradually becoming weaker in the following 2 or 3 years. After this period, all volcanic manifestations cease, starting a new eruption, after an irregular period of time that normally lasts for several years, in other parts of the same island. Subhistorical eruptions are represented by a single event: Tacande, Tacante or Montaña Quemada: VEI 2, 1470-92, 462 ha (unknown duration). Historical eruptions on La Palma occurred as follows: Tehuya, Tahuya, Tihuya, Roques de Jedey or Los Campanarios: VEI 2, 1585, 24×10⁶ m³, 400 ha, 84 days. San Martín, Tigalate or Tagalate: VEI 2, 1646, 26×10⁶ m³, 610 ha, 82 days. San Antonio: VEI 2, 1677-78, 66×10⁶ m³, 446 ha, 66 days. El Charco or Montaña Lajiones: VEI 2, 1712, 41×10⁶ m³, 535 ha, 56 days. San Juan (western vent of Llano del Banco and eastern craters of Nambroque, Hoyo Negro and Duraznero—the latter two jointly known as Las Deseadas): VEI 2, 1949, 51×10⁶ m³, 392 ha, 47 days. Teneguía: VEI 2, 1971, 31×10⁶ m³, 317 ha, 24 days. Tajogaite: VEI 3, 2021, 215×10⁶ m³, 1,237.3 ha, 85 days and 8 hours (Sept. 20 14:11 UTC—Dec. 13 22:22 UTC). Magmatic activity underneath Cumbre Vieja Partial fusion of the mantle occurs in the superior section of the upper mantle, between depths of 70 and 40 km. 3% magma is produced, and the remaining 97% is composed of peridotitic rock derived from the Earth's mantle. From 40 km upwards, the build-up of liquid rock is higher, with magma comprising about 10 to 15%. The rising diapirs intrude into fissures up until depths of 30 km, creating small magma pockets which exert an elevated pressure and create earthquakes. Between 30 and 15 km below the island, few earthquakes occur. Most earthquakes in La Palma are recorded between 15 and 10 km depth, at the Mohorovičić discontinuity, where the boundary between the oceanic crust and the Basal Complex of the island is located. A great concentration of magma is located here, which exerts high pressures on the oceanic crust and the insular edifice which fractures the crust and creates fissures, resulting in earthquakes. Landslide and mega-tsunami misconception Detailed geological mapping shows that the distribution and orientation of vents and feeder dykes within the Cumbre Vieja volcano have shifted from a triple rift system (typical of most volcanic ocean islands) to a single north–south rift. It is hypothesised that this structural reorganisation is in response to evolving stress patterns associated with the development of a possible detachment fault under the volcano's west flank. Such failures are due to the intrusion of parallel and sub-parallel dykes into a rift. This causes the flanks to become over-steep and this inevitably causes the structure of the volcano to become unstable to the point that catastrophic failure may occur, leading to a giant landslide along the detachment fault which trigger a potentially huge tsunami. There is no evidence beyond its surface expression that the 1949 section of the rift extends in a north–south direction, nor that there is a developing detachment plane. One such mega-tsunami resulted when ~3×10¹⁰ m³ of volcanic material collapsed, forming the Güímar Valle on Tenerife ~830 ka, leaving marine deposits located between 41 and 188 metres above sea level in the Agaete Valley of Gran Canaria. So, while it is true that such landslides have occurred in the past on most of the Canary Islands, it is important to note that these events are rare and occurred at large time intervals spanning many tens of thousands of years, and that it is almost impossible for a trans-oceanic mega-tsunami to be generated in the basin of the Atlantic Ocean by a failure of the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja. Unfortunately, most media are driven by sensationalism and report about it as if there was strong evidence that such a partial collapse of La Palma could occur in the somewhat near future—including potential horror scenarios such as mega-tsunamis devastating the east coast of the United States. There is, however, no scientific evidence to support this scenario. In fact, the section of the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja is far too stable to collapse within the next 10,000 years. The Güímar landslide is—reportedly—the only plausible source for the marine deposits in Gran Canaria’s Agaete Valley, but there is no indication that the tsunami propagated beyond Gran Canaria. In the worst-case scenario for La Palma, with the most massive slide that could happen, the waves would dissipate as they propagate into the Atlantic. A height of 40 m is predicted for some nearby island systems. For continents, the worst effects are in northern Brazil (13.6 m), French Guiana (12.7 m), Mid-Atlantic United States (9.6 m), Western Sahara (37 m), and Mauritania (9.7 m). This is not large enough to count as a mega-tsunami, with the highest prediction for Western Sahara comparable to the 2011 Japanese tsunami, so it would only be a mega-tsunami locally in the mid-Atlantic Ocean. Nevertheless, as was mentioned earlier, a failure of the western flank of Cumbre Vieja is extremely unlikely and probably impossible right now with the present-day geology. #tajogaite #cabezadevaca #montañarajada #cumbrevieja #lapalma #eruption #volcano

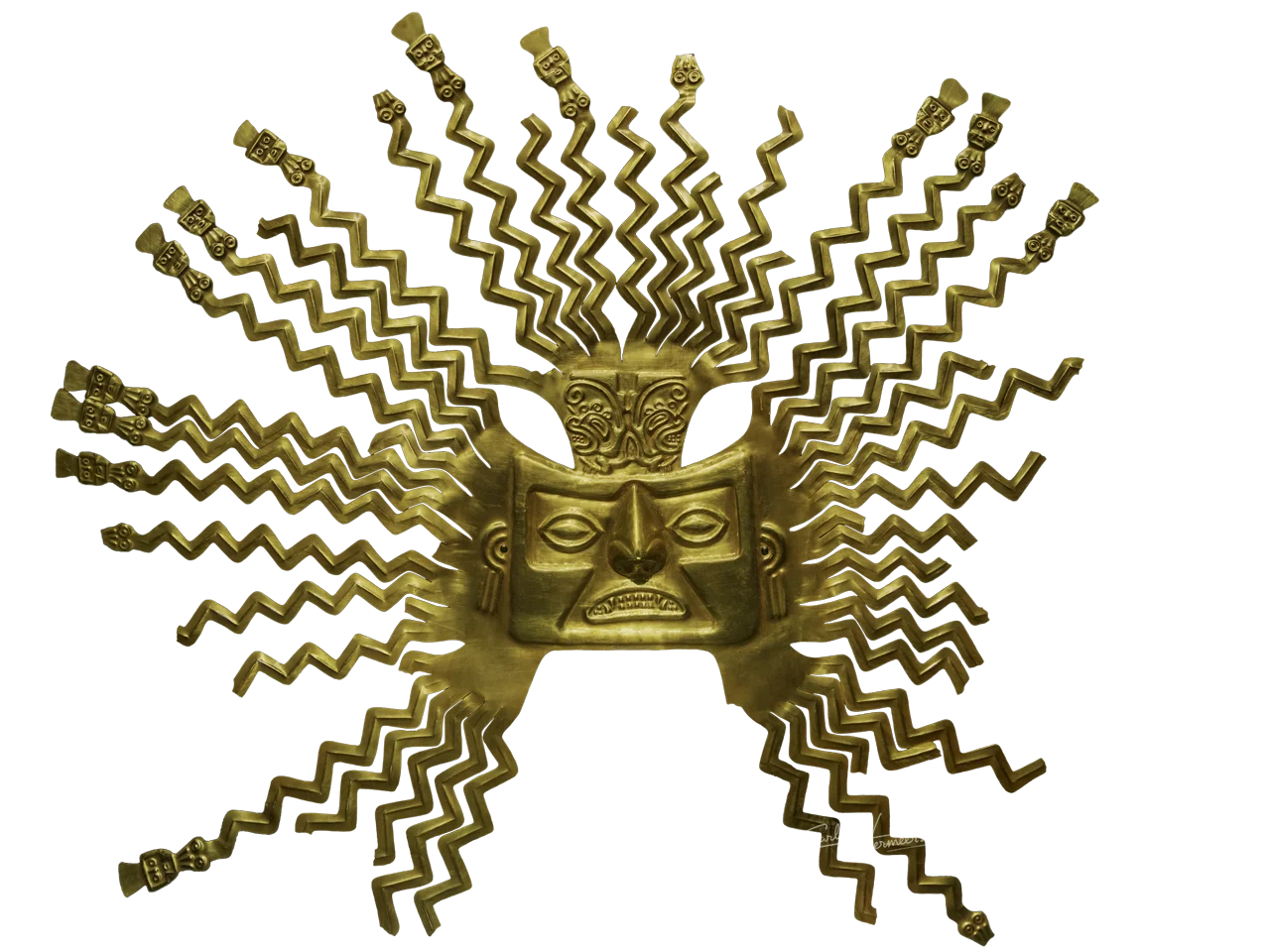

- Pre-Columbian History of Ecuador

Pre-Columbian Ecuador included numerous indigenous cultures, who thrived for thousands of years before the ascent of the Incan Empire. Las Vegas culture of coastal Ecuador is one of the oldest cultures in the Americas. The Valdivia culture in the Pacific coast region is a well-known early Ecuadorian culture. Ancient Valdivian artifacts from as early as 3500 BC have been found along the coast north of the Guayas Province in the modern city of Santa Elena. Several other cultures, including the Quitus, Caras and Cañaris, emerged in other parts of Ecuador. There are other major archaeological sites in the coastal provinces of Manabí and Esmeraldas and in the middle Andean highland provinces of Tungurahua and Chimborazo. The archaeological evidence has established that Ecuador was inhabited for at least 4,500 years before the rise of the Inca. Great tracts of Ecuador, including almost all of the Oriente (Amazon rainforest), remain unknown to archaeologists, a fact that adds credence to the possibility of early human habitation. Scholars have studied the Amazon region recently but the forest is so remote and dense that it takes years for research teams to survey even a small area. Their belief that the river basin had complex cultures is confirmed by the recent discovery of the Mayo-Chinchipe Cultural Complex in the Zamora-Chinchipe Province. The present Republic of Ecuador is at the heart of the region where a variety of civilizations developed for millennia. During the pre-Inca period people lived in clans, which formed great tribes, and some allied with each other to form powerful confederations, as the Confederation of Quito. But none of these confederations could resist the formidable momentum of the Tawantinsuyu. The invasion of the Inca in the 15th century was very painful and bloody. However, once occupied by the Quito hosts of Huayna Capac, the Incas developed an extensive administration and began the colonization of the region. The pre-Columbian era can be divided up into four eras: 1. Preceramic Period (end of the last glacial—4500 BC) Las Vegas Culture (9000—4600 BC) El Inga (9000—8000 BC) 2. Formative Period (4500—600 BC) Valdivia Culture (3500—1500 BC) Machalilla Culture (1500—1100 BC) Chorrera Culture (900—300 BC) 3. Period of Regional Development (600 BC—400 AD) La Bahía (300 BC—500 AD) La Tolita Culture (600 BC—200 AD) Guangala (100—800 AD) 4. Period of Integration and arrival of the Inca (400 AD—1532 AD) Los Manteños (600—1534 AD) Los Huancavilcas (600—1530 AD) Quitu-Cara Culture and the Kingdom of Quito (400—1532 AD) The Inca (1463—1532 AD) La Tolita Culture (600 BC—200 AD) The culture of La Tolita developed in the coastal region of Southern Colombia and Northern Ecuador between 600 BC and 400 AD. A number of archaeological sites have been discovered and show the highly artistic nature of this culture. Already extinct by the time of the Spaniards arrival, they left a huge collection of pottery artifacts depicting everyday life. Artefacts are characterized by gold jewellery, beautiful anthropomorphous masks and figurines that reflect a hierarchical society with complex ceremonies. Anthropomorphic golden funerary mask with platinum eyes. Anthropomorphic golden ornament. Golden and platinum ornament of a monkey head. Golden ornament with platinum and turquoise eyes. The Sol de Oro is the most prominent artifact from the La Tolita Culture. It is a sun-shaped mask dated between 600 BC and 400 AD. It was probably worn by a Shaman who knew the agricultural cycles, and used it for sowing and harvesting rituals. It has an anthropomorphic face with a jaguar mouth. The wavy rays bursting from the head are grouped into three bundles and are formed by slithering snakes tipped with human faces. At the base of the upper bundle of rays, there are two mythical crested animals that resemble dragons, which are common in the pre-Columbian art of the western South American coast, from Peru to Panama. The Sol de Oro is a piece of 21 karats and 284.4 g in weight, and its size is 64 by 40 cm. It is an embossed sheet fashioned from a natural alloy of gold and platinum. The provenance of the mask was until recently uncertain and was one of the most controversial among ancient Ecuadorian metallurgy. For years it was debated whether its origin lies in the Sig-Sig and Chordeleg area in the province of Azuay, or the area of La Tolita in the province of Esmeraldas. Finally, the results of neutron activation analysis have revealed the raw material has a coastal origin. Mythical four-eyed caiman statuette. Jaguar censer. Jaguar vase ornament. Head of a mythical creature. Statue of a priestess. La Bahía Culture (500 BC—650 AD) The Bahía culture inhabited modern Ecuador between 500 BC and 650 AD, in the area that stretched from the foothills of the Andes Mountains to the Pacific Ocean; and from Bahía de Caráquez to the south of Manabí. Jama-Coaque Culture (355 BC—1532 AD) The Jama-Coaque culture was settled in the North of modern-day Province of Manabí of Ecuador, mainly in the area between the Coaque and Jama rivers, from which it takes its name. It existed for approximately 2000 years, spanning from 355 BC to 1532 AD, with a possible subsequent permanence during the early colonial period of the country. The material culture of the Jama Coaque includes animal and human representations in stone and metal, but the best-known aspects of the Jama Coaque culture are its ceramic vessels and figurines probably made for ritual purposes. Depicting warriors, musicians, hunters, and dancers, the figures were mold-made and have appliqué decorations that were made in smaller molds. Some figures are attached to vessels, but most are freestanding. Jama Coaque figures share similarities with other coastal sites of the period, but are often more richly clothed and elaborately adorned. A vessel attached to a figure of a warrior wielding an atlatl (an Aztec loanword for "spear-thrower") and shield, pertaining to the Jama-Coaque culture, centred in northern modern-day Ecuador and dated between 355 BC and 1532 AD. A statuette of a step-pyramidal temple of the Jama-Coaque culture, centred in northern modern-day Ecuador and dated between 355 BC and 1532 AD. Manteño Culture (500—1532 AD) Silver mask with copper crown and crest, and golden nose ring with a quartz bead. Manteño culture, dated between 500 and 1532 AD. Small silver head with golden nose ring, belonging to the Manteño culture, centred in modern-day Ecuador and dated between 500 and 1532 AD. Embossed silver plaque depicting two beetles, of the Manteño culture, centred in modern-day Ecuador and dated between 500 and 1532 AD. Embossed silver pectoral of the Manteño culture, centred in modern-day Ecuador and dated between 500 and 1532 AD. The Manteño civilization was one of the last pre-Hispanic civilizations in modern-day Ecuador. The civilization mainly grew fruits and vegetables, such as maize, squash, tomatoes, and peanuts. They built their houses using straw, palm leaves, or a type of bamboo native to the region, with a stone foundation. The Manteños were also specialized in diving for 𝘚𝘱𝘰𝘯𝘥𝘺𝘭𝘶𝘴, a bivalve native to the warm waters of coastal Ecuador, and which was believed to be food of the gods. They also used its orange and purple shell as currency, and it was used in trade across regions as far north as Mexico. The Manteños were never conquered by the Inca, who let the Manteños buy their independence with the divine Spondylus that only they knew how to retrieve due to their diving abilities. Carchi-Nariño Culture (700—1700 AD) The Carchi-Nariño culture developed in the mountains of Nariño (Southern Colombia) and Carchi (Northern Ecuador) from 700 to 1700 AD. They harvested quinoa and raised llamas for agriculture and trade. They made artwork out of materials such as wood, strings, and wool. Their work sometimes took the form of shaft burials, some being extremely deep, as much as 50 m. Their pottery reached important artistic development, being recognizable by its forms and decoration, emphasizing the negative painting or positive bicolor. Their jewelry work stands out for the large gold pectorals, nose rings, discs and plaques, all made with fine gold sheets and with complex geometric designs. External links Museo Nacional del Ecuador (MuNa)

- Tacande

La Palma's Cumbre Vieja volcano eruption of 1470

Other Pages (23)

- Carlos V Studios | Northwestern Andean montane forests

Northwestern Andean montane forests The Northwestern Andean montane forests is an ecoregion on the western slope of the Andes mountains, in western Ecuador and Colombia. This ecoregion is part of the Northern Andean Montane Forests global ecoregion, in turn located within the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome, in the neotropical realm. Both flora and fauna are highly diverse due to the effect of alternating glacial and inter-glacial periods, which created isolated pockets of warm and cool zones respectively, and the consequent formation of endemisms therein. Since the environment is hospitable to humans, the habitat has been drastically affected by farming and grazing since the Pre-Columbian era. The high biodiversity and the anthropic impact these forests possess qualify it as part of the tropical Andes biodiversity hotspot. comments debug Comments Write a comment Write a comment Share Your Thoughts Be the first to write a comment.

- Carlos V Studios

Tajogaite eruption The Tajogaite volcano of the Cumbre Vieja mountain ridge on the Island of La Palma violently erupting during the collapse of its pulsating Hawaiian vent. See Blog Post See Gallery Masked trogon A male masked trogon (Trogon personatus assimilis ) scanning the vegetation for insects in the canopy of the Northwestern Andean montane cloud forest of Ecuador. See Gallery Cuyabeno The ecologically eclectic forest of Cuyabeno. Despite being located at the foothills of the Andes, it has a network of inundated forests, lakes and creeks, leading to a different species composition than other areas in the Amazon. See Gallery Marine iguana After foraging for algae in the cold waters of the island of San Cristóbal, this marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus mertensi ) decided to sunbathe on the rocky shore. See Gallery Griffon vulture A griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus ) taking flight from a cliff in Monfragüe, where the number of pairs reaches over 600. See Gallery Cascade des Bésines This idyllic waterfall in the French Pyrenees is located in the middle of the mountains between France, Spain and Andorra. See Gallery Chimpanzee Baboon Island in the River Gambia is home to the most northwesterly population of chimpanzees, reintroduced in 1979 and currently comprised by ca. 100 individuals. See Gallery Great white shark A lonesome great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias ) swimming in vast pelagic waters, bound for its next prey-rich coast. See Gallery S ol de Oro A 2500 year old anthropomorphous mask manufactured from a naturally occurring alloy of platinum and tumbaga by artisans of the Tumaco-La Tolita culture. See Blog Post See Gallery Companies and organisations I have worked with: 1/9