The poster of Paleoconéctate. Slide for details. All illustrations and photos are created by myself, unless noted otherwise. Design and diagrams are own work.

On March 28th 2019 was the first congress of the paleontology project “Paleoconéctate”, which was held at the Faculty of Journalism in the University of La Laguna. The investigation group is integrated by paleontologists Dr. Carolina Castillo Ruiz –the president of the act– and Penélope Cruzado Caballero –the secretary of organization–, as well as other scientists of the University of La Laguna and the Museo de la Naturaleza y el Hombre, and I have the honour to be part of it.

I’m proud to present the above poster which I created for Paleoconéctate. The poster tells the story of our planet since its formation up until the present, while contextualizing the major natural and historical events that took place in the Canary Islands. The photos (unless stated otherwise), illustrations, diagrams and parts of the text are my own work, created exclusively for the poster of this project.

Mesozoic

(252.17 Ma—66.0 Ma)

The Permian–Triassic extinction, which happened about 252 million years ago, is colloquially known as the Great Dying, and with good reason, since it is the Earth's most severe known extinction event, with up to 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species becoming extinct. This event marked the transition of the Paleozoic to the Mesozoic, as well as the wake of the Triassic period. The biosphere was so severly impoverished, it was well into the middle of the Triassic before life recovered its former diversity. The remaining therapsids and archosaurs were the chief terrestrial vertebrates during this time. A specialized group of archosaurs, dinosaurs, first evolved in Gondwana, but it wasn't until the Jurassic when they became the dominant terrestrial animals.

The Canary Islands are located in the North Atlantic Ocean, which opened up 175 million years ago during the Lower Jurassic due to rifting that separated Laurasia into North America and Eurasia. Gondwana still remained assembled until 145 million years ago when the separation gave rise to the South Atlantic Ocean. The oldest islands of the Canaries were formed 20.2 million years ago and had therefore not yet formed during the Mesozoic. The oceanic crust from which they emerged, however, did exist during the Cretaceous and half of the Jurassic, when dinosaurs were the dominant terrestrial animals.

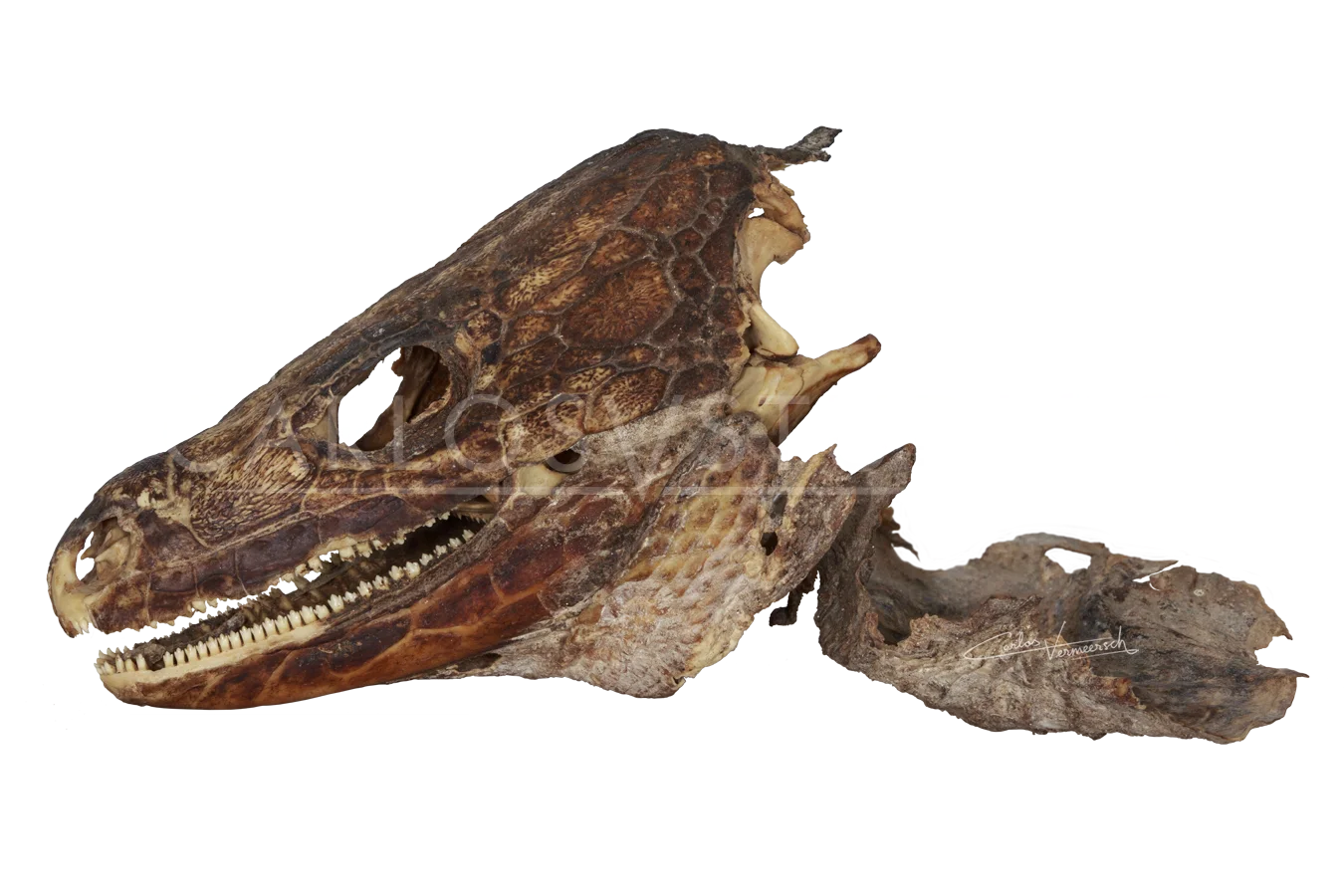

66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous, the sudden Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) mass extinction event mercilessly wiped out three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, not leaving a single tetrapod heavier than 25 kg (55 lbs.), only with the exception of ectothermic animals such as crocodilians and the leatherback sea turtle. It marked the end of the Cretaceous period and with it, the entire Mesozoic Era, opening the Cenozoic Era that continues today.

Due to the great length of time between the K–Pg extinction and the emergence of the first of the Canary Islands (roughly 45 million years), and since no fully marine non-avian dinosaurs are known to have existed (some members of the Spinosauridae family were only semiaquatic and preferred shallow aquatic environments such as estuaries), no non-avian dinosaurs can possibly be unearthed in the Canary Islands. Most animals recovered from those periods are foraminifera and ammonites, such as Partschiceras sp., in the island of Fuerteventura, which has Mesozoic Era rock outcroppings due to the uplifting of oceanic crust on top of which the Canary Islands would one day form.

Paleogene and Neogene

(66.0 Ma—2.58 Ma)

It is not until the early Miocene, 20.2 million years ago, when the first islands started to emerge above the sea level. This marks the appearance of vertebrate animals in the fossil record of the islands. Even though the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction is long since passed, the Canaries have never been devoid of dinosaurs at all, nor has most of the world for that matter, even to this day. Small volant theropods, like the famous Archaeopteryx lithographica from Germany, appeared in the Jurassic period and have been around ever since, surviving the sudden mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. These surviving dinosaurs are known as birds. As a result of their high dispersal capabilities, birds are much more common on islands than are poorly dispersing taxa, like mammals and amphibians, and are likewise the first vertebrates to colonize newly emerged oceanic islands.

The emergence of the Canary Islands occurred shortly after the rise of one of the greatest predators the oceans have ever seen, Carcharocles megalodon, around 23 million years ago. It was 18 meters (59 ft) long and weighed up to 100 tonnes. It was a very successful predator that lived until the late Pliocene and specialized on hunting small whales, usually under 5 meters long. C. megalodon is usually depicted as a stockier version of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), though it is believed it might have been similar to the sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus) or even the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) due to their overlap in size ranges. The most common fossils of C. megalodon are its huge teeth, which they have left all over the world’s oceans and seas, including the Canary Islands, indicating it had a cosmopolitan distribution.

Megalodon's teeth are characterized by a triangular shape, robust structure, fine serrations, a lack of lateral denticles –which were still present in its ancestor Carcharocles chubutensis–, and of course their enormous size, the largest tooth ever found measuring 19.37 cm (7 5/8 in). The large jaws could exert a bite force of up to 110,000 to 180,000 newtons (25,000 to 40,000 lbf). Their teeth were built for grabbing prey and breaking bone. C. megalodon had 46 front row teeth, 24 in the upper jaw and 22 in the lower jaw. Most sharks have at least six rows of teeth, so a Megalodon would have had about 276 teeth in it's mouth at any given time. All sharks shed their teeth during their lifetime or as they grow, and it's estimated that an adult C. megalodon may have shed as many as 20.000 teeth during it's lifetime. This makes them one of the most common fossils of the Neogene. So much so, that these teeth have been found throughout history. Pliny the Elder, around 70 AD, thought they fell from the sky during lunar eclipses, and during the Middle Ages they were known as glossopetrae or “tongue stones” and thought to be the tongues of serpents that Saint Paul had turned to stone while visiting Malta. They were believed to have magical properties, most notably the ability to counter-act toxins of many kinds –from a snakebite to poison slipped by an assassin into a king's wine chalice– and were therefore worn by many medieval nobles and statesmen as amulets. The largest shark that has ever existed lived alongside an equally large sperm whale, known as Livyatan melvillei, with which it competed for prey. But the reason for its extinction 3.6 million years ago was due to a decreasing number of adequate prey and increased competition from other predators, like the ancestor of the killer whale and the great white shark.

As the primitive Canary Islands grew larger, Fuerteventura along with Lanzarote formed a larger island called Mahan and remained fused until the Holocene. When sea levels dropped, the African and Canarian coastlines were closer together, which probably would’ve facilitated to some degree the arrival of larger vertebrates to the archipelago as is attested by the fossil record, including ratite eggs, boa vertebrae and tortoises. Some of the animals that were able to arrive and thrive in the islands suffered insular gigantism. The tortoises attained lengths comparable to those of the Aldabra tortoises (Aldabrachelys sp.) and the Galápagos tortoises (Chelonoidis sp.). Remains have been found in southern Tenerife, on Gran Canaria and also on Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, but these taxons remain undetermined. Most fossils are of bones and shells, as well as nests of fossilized eggs. The species from Tenerife, Geochelone burchardi, had a shell length of 65-94 cm, whereas G. vulcanica, from Gran Canaria, had a slightly shorter shell of 61 cm. Both species got extinct well before the humans first appeared in the archipelago, possibly due to volcanic eruptions; inhabiting the islands from the Miocene until the Upper Pleistocene.

Cuaternary

(2.58 Ma—0)

Lizards of the subfamily Gallotiinae had colonized the islands shortly after they formed, between 17 and 20 million years ago, and radiated throughout the archipelago, growing in a wide variety of sizes. It is still a matter of debate whether the large lizards of the Canary Islands had suffered gigantism after colonizing the islands, or if they were already large before their arrival and some evolved smaller to occupy other niches. Some scholars favor the latter theory due to the discovery of older fossil lizards of the Gallotiinae family from Miocene mainland Europe of similar large sizes. The last common ancestor of giant lizards of the Canary Islands (G. intermedia, G. bravoana and G. simonyi) expanded 3 million years ago from La Gomera and the 3 islands that would one day become Tenerife towards La Palma and El Hierro. The giant lizard from Gran Canaria, despite its big size, is in fact a more basal taxon that diverged 11-13 million years ago. At least two giant lizards species got extinct in the last two millennia, probably due to hunting by indigenous peoples: Gallotia goliath (Gallotia maxima, a junior synonym) from Tenerife and Gallotia auaritae from La Palma.

Due to the volcanic origin of the Canary Islands, they are mined with natural traps: lava tubes. Some of them are among the largest in the world. Lava tubes are conduits formed by flowing lava which moves beneath the hardened surface of a lava flow, because lava cools down first on the outside while the interior remains hot much longer. The tubes drain lava from a volcano during an eruption and get extinct when the lava flow ceases, leaving a long cave after the rock has cooled. Parts of the roof of the tube will then collapse under its own weight, and unfortunate animals like giant rats and lizards can fall into these crevices never to see the light of day again. However, these tubes offer the perfect environment for the preservation of these remains, like articulated skeletons as well as natural mummification.

Another group of extinct animals has also reached the islands: murines, i.e. rats and mice. Rats are known to commonly achieve gigantism on oceanic islands, such as the also extinct Megaoryzomys curioi from the Galápagos Islands, but some species also attain big sizes in the mainland, like Cricetomys gambianus, widespread in Sub-Saharan Africa. Two species of giant rats from the Cuaternary have been described, one in Tenerife and another one in Gran Canaria. It is believed the rabbit-sized species from Tenerife, Canariomys bravoi, was arboreal and linked to the humid Monteverde forests in the north of the island, whereas C. tamarani, the species from Gran Canaria, was more slender and had a burrowing lifestyle, preferring open spaces. Both species were herbivorous and probably ate soft vegetables like some roots, ferns and berries.

During the Pleistocene, the islands were also home to species of birds with reduced flight ability, like Chloris triasi from La Palma, and flightless birds like Emberiza alcoveri from Tenerife. For the sea-faring birds that arrived to the Canaries, the islands were a utopia, filled with plenty of food and devoid of predators. Over time, the birds lost their ability to fly because they simply had no use for it. This evolutionary story is actually not limited to the Canary Islands, but a common fenomenon which repeats itself on oceanic islands. Despite birds commonly losing the ability to fly in oceanic islands, these are two of the very few flightless passerines known to science, all of which are now extinct. The other flightless passerines being three species of New Zealand wrens: Lyall's wren (Traversia lyalli), the long-billed wren (Dendroscansor decurvirostris) and the stout-legged wren (Pachyplichas yaldwyni).

Chloris triasi was very similar and closely related to the European greenfinch (Chloris chloris). However, its head was larger and broader and its bill was about 30% larger. Its legs were very long and robust, but compared to the greenfinch its wings were shorter. This might have been an adaption to more terrestrial habits in monteverde forests. Several remains have been found, including a relatively complete skull. Emberiza alcoveri also has a close relative from Europe, the yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella). This species is distinguishable from other Emberiza sp. due to its larger size, longer legs, shorter wings, and a differently-shaped bill. These features indicate that it was a flightless ground dweller. 8 skeletons have been found of this species.

Possibly over 2000 years ago, Berbers arrived from Northwest Africa to the Canary Islands. Over the centuries, they differentiated into 7 distinct cultures, one on each island, with their own religion and social, political and economical structures. Upon the arrival of humans to the Canary Islands, they drove many endemic animal species, including the largest lizard species (Gallotia goliath and G. auaritae), to extinction due to hunting and the introduction of domestic animals. Nonetheless, several giant lizard species, like G. intermedia, G. bravoana and G. simonyi have survived the arrival of humans by retreating to remote cliffs, but were forced to adapt and attain smaller sizes. However, Gallotia stehlini from Gran Canaria not only managed to survive, but thrive in human presence and be the biggest of the remaining lizards in the Canary Islands.