Scientific name: Gallotia goliath & G. auaritae

Family: Lacertidae

Snouth-to-vent length: 40-50 cm

Total length: 120-150 cm

Distribution: Tenerife, La Palma (respectively)

Habitat: Xerophytic vegetation and thermophilous forests up to 900 m a.s.l.

Origin category: Endemic species

Conservation status: Extinct

The genus Gallotia is endemic to the Canary Islands and it belongs to the subfamily Gallotiinae, the sister taxon of Lacertinae, which in turn has a much larger distribution—primarily Mediterranean but also spreading eastward into the Middle East and Central Asia, with one genus (Takydromus) in Far East and Southeast Asia. This subfamily only has two genera, Gallotia and Psammodromus (6 species), found in Europe and North Africa. It was once more widespread and present in the continent. This is attested by findings in Germany, where Miocene and Oligocene crown lacertids have been discovered, Pseudeumeces cadurcensis (ca. 30-20 Ma) and Janosikia ulmensis (22 Ma), respectively. These fossil taxa show that large body size was already achieved on the European mainland by the early Miocene.

Around 23 Ma, the first islands of the Canary Islands started emerging, less than 100 km off the Moroccan coast. These islands lied right ahead of the Sous, Massa and Drâa river deltas in Western Morocco. Throughout millions of years, these three rivers carried floating logs that had lizards, turtles, rodents and other small animals on them, some of which were able to survive a voyage through the Atlantic Ocean onto the shores of the primitive Canary Islands.

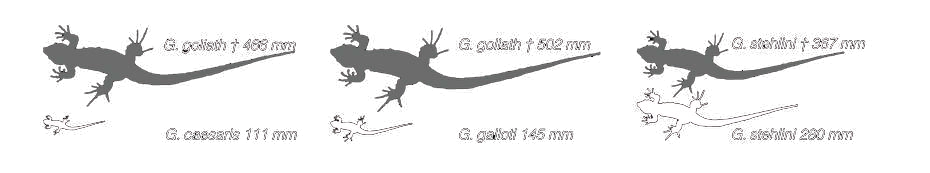

The genus Gallotia appeared shortly after the emersion of these first islands, and the last common ancestor of the giant lizards of the Canary Islands (of the G. intermedia/bravoana/simonyi clade) expanded 3 million years ago to La Gomera and the three islands that existed prior to the formation of Tenerife (Roque del Conde, Teno and Anaga). Finally, from La Gomera it reached El Hierro 850 thousand years ago. At present, Gallotia contains some of the largest lacertids in the world. However, several extinct species attained much larger sizes, even doubling the largest extant Canary giant lizards.

There are at least two extinct giant lizards in the Canary Islands — G. goliath from Tenerife (a.k.a. G. maxima, a junior synonym) and Gallotia auaritae from La Palma. Remains of similarly sized lizards have been found on El Hierro and La Gomera, but those might simply be large ancestors of the extant lizards there — G. simonyi and G. bravoana (synonymous with G. gomerana) respectively, as occurred with G. stehlini in Gran Canaria which used to reach a greater size. It is possible that remains of extinct giant forms will eventually be discovered on Fuerteventura and Lanzarote.

Tenerife Giant Lizard

Gallotia goliath

The Tenerife giant lizard, or G. goliath, inhabited the lower and middle parts of the island of Tenerife. It was not only the largest of all the so-called giant lizards of the Canary Islands but also the largest known lacertid of the fossil record, reaching a length of approximately 1,25 m (4 ft). It was most likely endemic to Tenerife and its closest living relative is probably G. intermedia, also from Tenerife.

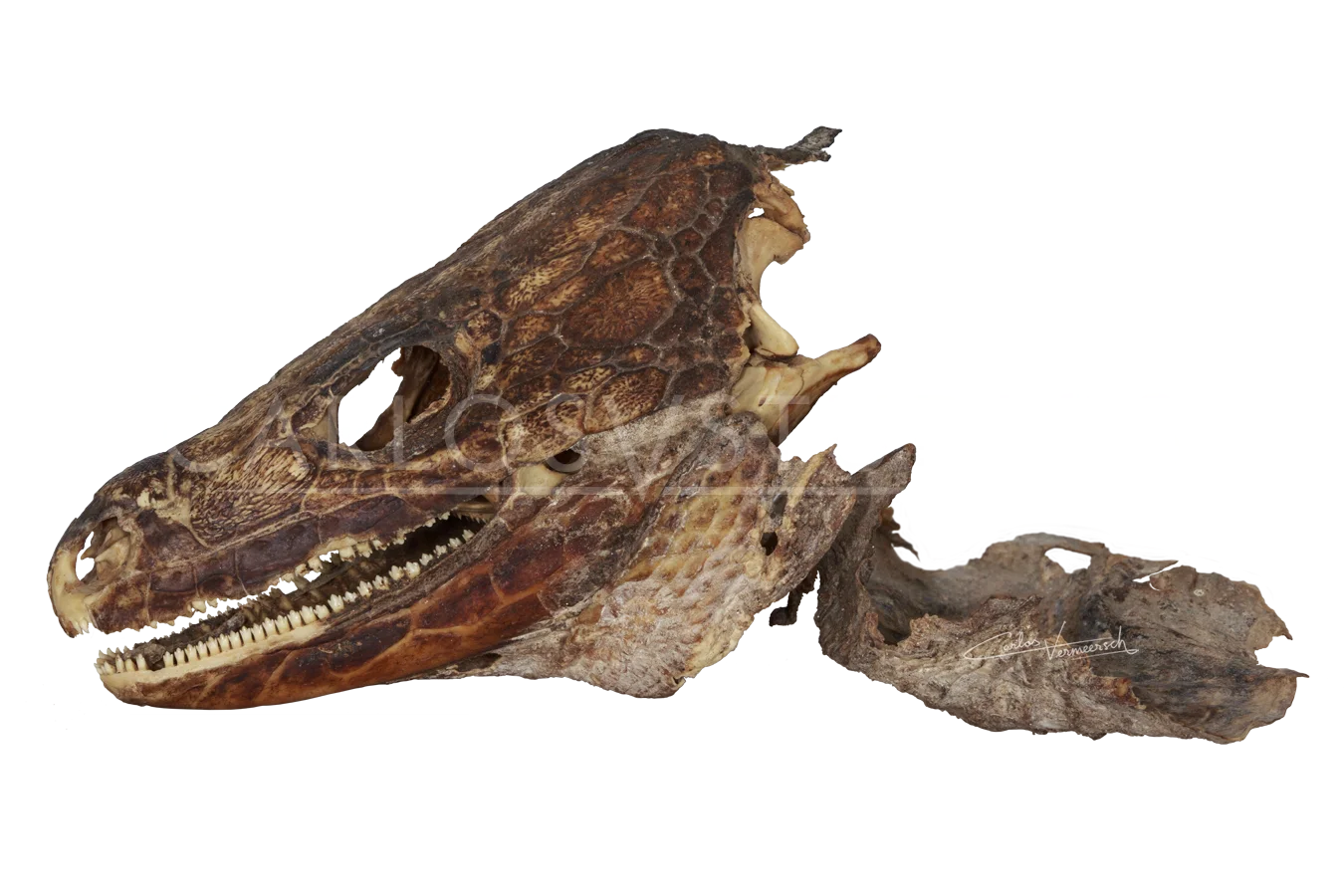

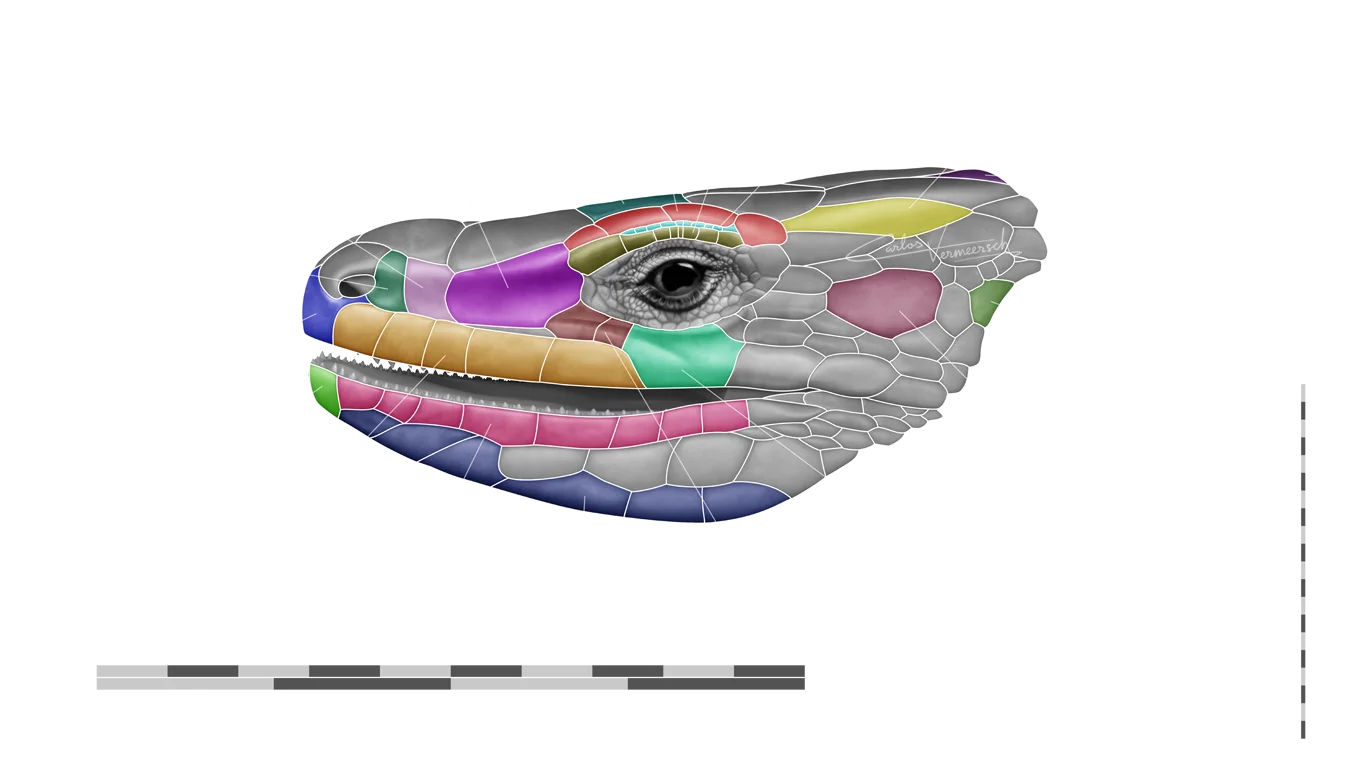

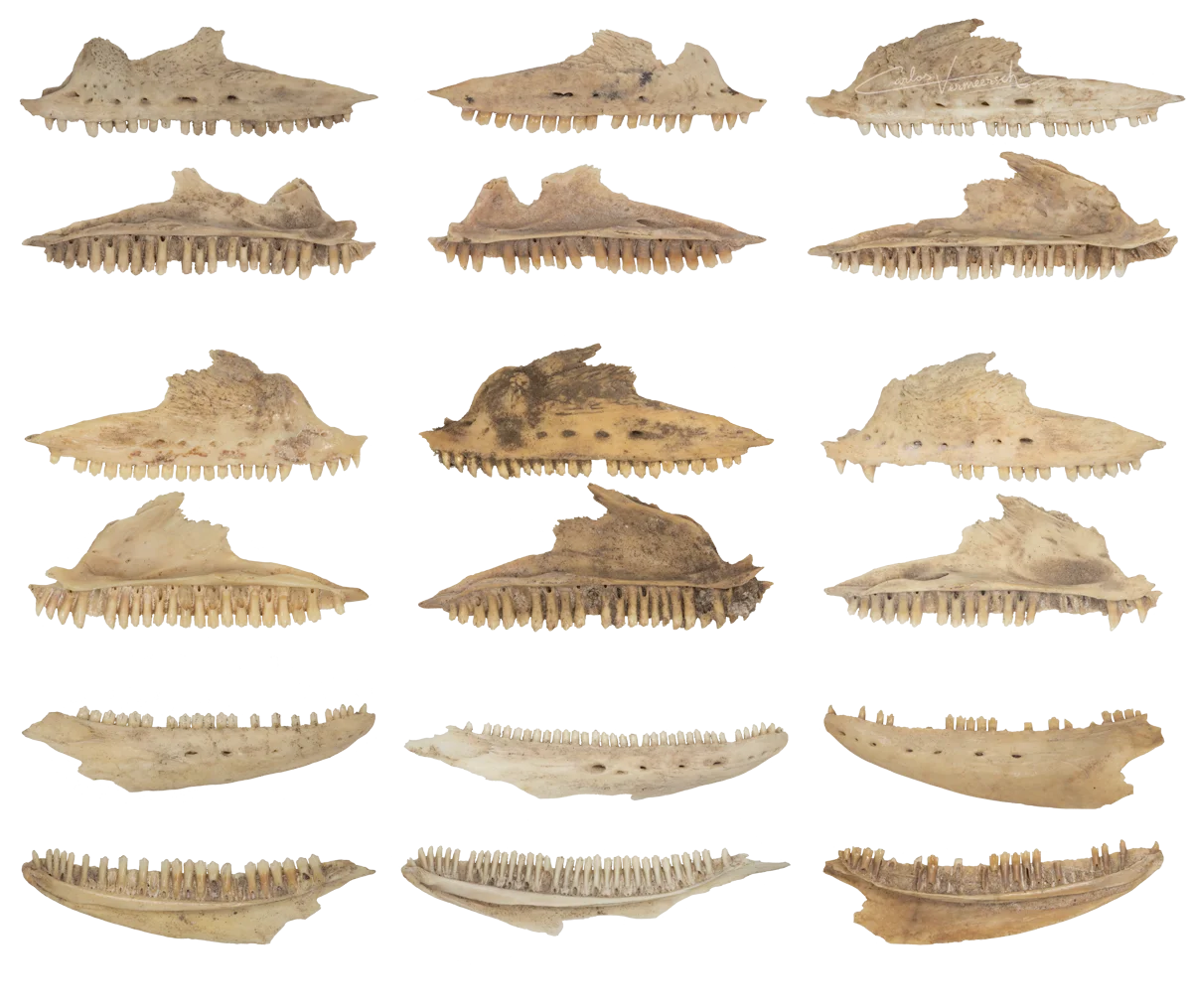

Overall, it was a big, sturdy lizard with strong, muscular legs and a proportionally short and thick tail. It had a very large and robust head broadened towards the base, which gave it a somewhat flattened look. They reached a snout-to-vent length of ~50 cm (19.6 in) and a total length of 120 to 125 cm (47.2-49.2 in), but based on the finding of a 13.5 cm (5.3 in) skull in 1952, there could have been even larger specimens. Primarily carnivorous as juveniles, they tended to become herbivorous as they grew and reached maturity, although they probably wouldn't have rejected an easy prey from time to time. Its jaws were capable of delivering a powerful bite, but this force was most likely used as a defense towards predators or to establish a dominance hierarchy between males. The dentary and maxilla beared tricuspid symmetrical teeth, as opposed to those of G. galloti, G. atlantica and G. caesaris, that have bicuspid or monocuspid cylindrical teeth. The numerous teeth gave it a saw-like appearance, which is comparable to that of iguanids, skinks and lacertids that have a plant-based diet.

Due to the volcanic origin of the Canary Islands, they are mined with natural traps: lava tubes. Tenerife is home to Europe's largest lava tube and the 5th largest in the world, the Cueva del Viento-Sobrado caves. Lava tubes are conduits formed by flowing lava which moves beneath the hardened surface of a lava flow, because lava cools down first on the outside while the interior remains hot much longer. Tubes drain lava from a volcano during an eruption and get extinct when the lava flow ceases, leaving a long cave after the rock has cooled. Parts of the roof of the tube will then collapse under its own weight, and unfortunate animals like giant rats and lizards can fall into these crevices never to see the light of day again. However, these tubes offer the perfect environment for preservation of these animals, as well as natural mummification. Several mummified specimens of G. goliath have survived to our days.

La Palma Giant Lizard

Gallotia auaritae

The La Palma giant lizard, or Gallotia auaritae, is endemic to La Palma. It owes its name to the aborigines of La Palma, the Benahoarites or Auarites, who used to hunt them for food. It reached similar lengths to that of G. goliath. From the structure of its skeleton, the La Palma giant lizard is known to be a large, robust lizard with well developed, muscular legs, and slightly shorter than G. goliath, reaching a snout-to-vent length of 40 to 44 cm (15.7-17.3 in). Male La Palma giant lizards are generally larger than females, with larger, sturdier heads. G. auaritae also had tricuspid and symmetrical teeth, but had considerably less maxillary and dentary teeth than similarly sized G. goliath from Tenerife, bearing between 18 and 33 teeth in the dentary.

A low-resolution photograph of a lizard, claimed to be G. auaritae, was published in the Bulletin of the Spanish Herpetological Society (Mínguez et al., 2007; Boletín de la Asociación Herpetológica Española, 18, 11–13). Despite the unreliability of the evidence and that since 2007 there have been no new reports, IUCN has given credit to this supposed discovery, categorizing G. auaritae as Critically Endangered in the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The authors indicate that the photograph is not that of G. galloti palmae because the back is very dark and lacking any markings and the gular region is not blue. Nonetheless, the coloration in G. g. palmae is very variable and can present bright yellowish-green stripes on its back or have a dull coloration, similar to the case of G. galloti subspecies in Tenerife. The dull-colored variation of G. g. palmae strikingly resembles the lizard on the photo. Moreover, some blue is visible in the gular region and above the fore limbs. Evidence for its existence is no stronger than that for any cryptid such as the Loch Ness monster.

Extinction

Both Gallotia goliath and G. auaritae coexisted with the indigenous Berber peoples of the Canary Islands, since ca. the year zero when they arrived. The moment and reason for their extinction, on the other hand, are not clear. It might have happened shortly after the arrival of the Berbers from North Africa. The indigenous berbers introduced farm animals that could've produced their extinction. Additionally, the Benahoarites from La Palma are known to have hunted them for food, as attested by a burnt partial dentary and a maxilla found near an archaeological site, and are exclusively found associated with pottery fragments of Phase I which is dated to before Christ, and not with later, more advanced pottery.

However, there's a small chance they might not have disappeared until recent times, since some testimonials survive from the 15th century of very large lizards, when the islands were being conquered by the Crown of Castile and settled by colonists. Gadifer de La Salle, a French knight and crusader who conquered and explored the Canary Islands with Jean de Béthancourt for the Kingdom of Castile, wrote in 1407:

"The waters are good and there is a great number of animals, that is, pigs, goats and sheep. And there are many large lizards the size of a cat, but they are harmless and do not possess any venom."

Even though the text could be speaking about the surviving lizards Gallotia stehlini, G. simonyi, G. bravoana and G. intermedia, these species were presumably only capable of achieving such sizes in prehistorical times. Only new discoveries will be able to shed light on this matter.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Carolina Castillo Ruiz, palaeontology professor at the University of La Laguna.

Dr. Gloria Ortega Muñoz, entomologist and curator of the Museo de Naturaleza y Arqueología.

Sources

Fossil lizard from central Europe resolves the origin of large size and herbivory in giant Canary Islands lacertids. Čerňanský, Klembara & Smith. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, April 2016.

Divergence times and colonization of the Canary Islands by Gallotia lizards. Cox, Carranza & Brown. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, August 2010.

The signatures of Anthropocene defaunation: cascading effects of the seed dispersal collapse. Néstor Pérez-Méndez, Pedro Jordano, Cristina García & Alfredo Valido. Scientific Reports, December 2015.

Discovery of mummified extinct giant lizards (Gallotia goliath, Lacertidae) in Tenerife, Canary Islands. Carolina Castillo, Juan C. Rando, & José F. Zamora. Bonner zoologische Beiträge, October 1994.

External links

Museo Arqueológico Benahoarita (Cabildo de La Palma)